The Art of Politics Was Surely Welcome in the San Diego Theater Scene of 2019

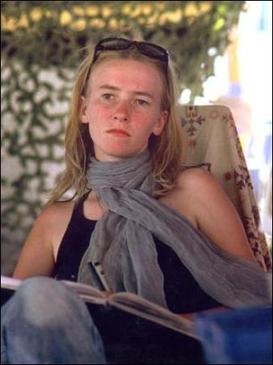

Rachel Corrie contemplates the state of the world and her place in it. The Olympia, Wash. native, killed by an Israeli soldier in 2003, would be emphatically memorialized onstage. Photo by The Rachel Corrie Foundation for Peace and Justice.

Besides, San Diego Repertory Theatre already won the lifetime achievement Marty for Best Locally Produced Entry in the History of the Universe. That was three seasons ago, when the company staged Disgraced, a show that marked the rift over Muslim identity in the West.

Pakistani American playwright Ayad Akhtar’s treatise (which won the 2013 Pulitzer Prize) is an absolute masterpiece, and director Michael Arabian knew it, mining every square inch of potential into a bona fide phenomenon I’ve not seen before and perhaps may never experience again.

My, oh my.

… [T]heater is a colossally political medium, especially in the strictest sense of the word.

But my relatively sparse agenda this year did reflect a lot of common ground. Broadway San Diego’s Fiddler on the Roof and Miss Saigon, North Coast Repertory Theatre’s A Walk in the Woods and Gabriel and Lamb’s Players Theatre’s CHAPS! had their war-related plot points and political adornments — and although each sought a different raison d’etre amid different criteria (and results), local theater was the better for them.

If politics doesn’t yank your chain, chances are you’re not a real theater person — because by its definition, theater is a colossally political medium, especially in the strictest sense of the word.

San Diego missed an opportunity to drive the point home a few years ago, but it wasn’t for lack of interest. The play in question is My Name Is Rachel Corrie, based on the e-mails and diaries of peace activist Rachel Ailene Corrie, an Olympia, Wash. native killed by an Israeli soldier.

Rachel Corrie lies mortally wounded following an incident wherein she was struck with a bulldozer by an Israeli soldier. Those who tended to her reported that her eyes were wide open and that her last words were, “I think my back is broken.” Photo by International Solidarity Movement.

The story recounts Corrie’s March 16, 2003 attempts to thwart the soldier’s advance toward a Palestinian doctor’s home he was sent to level via armored bulldozer at the Gaza Strip town of Rafah, which Corrie was visiting as a senior at Olympia’s Evergreen State College. Witnesses say that Corrie, 23, was in plain sight of the operator, bullhorn in hand, when he struck and backed over her (some say twice), breaking both legs and both arms, impaling her face, fracturing her spine and inflicting massive internal injuries.

She died in a hospital some 20 minutes after the incident.

“Sometimes,” she had reflected in a radio interview days earlier, “I sit down to dinner with people, and I realize there is a massive military machine surrounding us, trying to kill the people I’m having dinner with.”

… Sueko’s comments came on the heels of the New York Theatre Workshop’s abrupt cancellation of the show in 2006.

Seema Sueko, deputy artistic director at Washington, D.C.’s Arena Stage, was artistic director at San Diego’s defunct Mo’olelo Performing Arts Company when the Corrie play was published, speaking at length to San Diego CityBeat about perhaps acquiring the rights.

While nothing transpired on that front, Sueko did reflect on the play’s plot points, such as Corrie’s relationship with her mom and dad, the guys she dated and, mostly, her place in the world.

This gathering is not as convivial as it may look. Those of you who saw San Diego Repertory Theatre’s outstanding ‘Disgraced,’ from 2016, know what we mean. Photo by Daren Scott.

It’s critically important to note that Sueko’s comments came on the heels of the New York Theatre Workshop’s abrupt cancellation of the show in 2006. Viner, who had a ticket to New York in hand when the Workshop made its announcement, wasn’t having it.

Corrie, she wrote in the March 1 Guardian, “was to be silenced for political reasons… [I]f a voice like this cannot be heard on a New York stage, what hope is there for anyone else?”

It’s the “voice like this” part that underscores theater’s role as a political animal. Corrie’s mother Cindy described the family as “average Americans—politically liberal, economically conservative, middle class.” As for Corrie herself, she’d take several arts courses and took a year off from her studies to work as a volunteer in the Washington State Conservation Corps, later spending three years making weekly visits to mental patients.

In her senior year, Corrie would congregate with International Solidarity Movement members in an effort to prevent the Israeli army’s demolition of Palestinian homes. The unthinkable followed in relatively short order.

Meanwhile, there’s nothing whatsoever that suggests Corrie’s potential for recruitment into a pro-Palestinian cause — these “middle-class, average Americans” were otherwise nondescript on the popular landscape. A few altered circumstances and the winds of serendipity led to a young woman’s brutal death in a world hotbed and another nine years in court, wherein an Israeli judge ruled in August of 2012 against the Corries following a civil lawsuit over the country’s investigation of the event.

… this country’s political underside is rife with populist truth …

If such a grave misfortune can indiscriminately catapult one ordinary family into the international spotlight to this extent, it can do the same to all. Add the theater’s eagerness to employ whatever degree of poetic license, and this country’s political underside is rife with populist truth, which is exactly its function among those who seek it.

I like the fact that many politics-tinged pieces found themselves onto local stages this year. None of them was a Disgraced, but very few plays are. Meanwhile, those who plan the theater’s seasons showed a keen awareness of the art’s capacity for reflection, however discomfiting.

Today’s stage is most certainly not your father’s, and God willing, it never will be again. San Diego’s artistic directors and dramaturges did an admirable job in ensuring as much in 2019.