The Empyrean Heights of Richard Goode’s Piano Recital

International piano competitions spew forth freshly minted virtuosos with such regularity, it is difficult to keep abreast of the latest sensation. But the sizable audience that drove out to the Sorrento Valley to hear Richard Goode play his solo recital Friday (November 10) was casting its vote for the interpretative depth and emotional maturity that comes after spending a lifetime with the repertory.

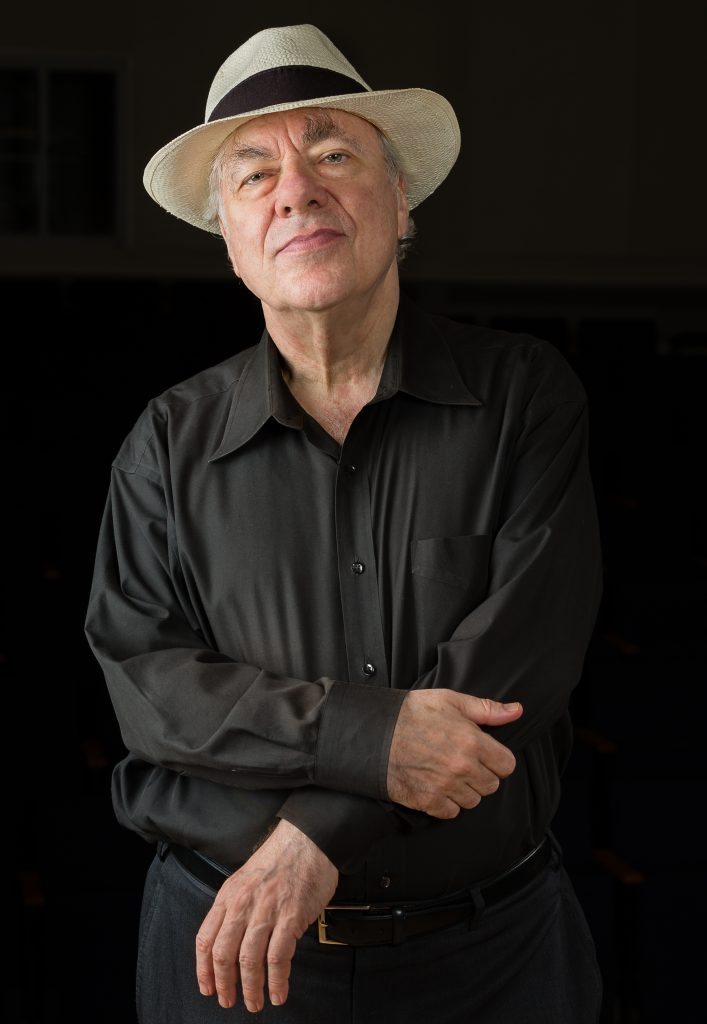

And Goode did not disappoint.Offering a program of music the 74-year-old Goode has long championed–J. S. Bach, Beethoven and Chopin—he added the exquisite set of Six Little Piano Pieces, Op. 19, by Arnold Schoenberg for good measure. A pianist’s pianist with a deep and miraculously even touch, Goode quickly ascended to empyrean heights with his opening set of four Preludes and Fugues from second volume of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier.

In the opening F-sharp Minor Prelude and Fugue, BWV 883, Goode’s glowing counterpoint ebbed in gentle surges, shaped with delicately nuanced dynamic contrasts, and his crystalline trills gently animated the subject of the Fugue. In the A Minor Prelude and Fugue, BWV 889, his relentless legato touch gave way to more pronounced articulation, especially in his treatment of the A Minor’s angular, assertive fugue subject. Goode flaunted his sleek keyboard prowess in the rapid perpetual motion Preludes of BWV 884 and BWV 892, but chose a courtly, elegant exposition for the broad phrases of the closing fugue of the set, the B Major Fugue, BWV 892.

As masterful as Goode’s Bach sounded, he appeared even more at home in Beethoven’s quirky, virtuosic A Major Piano Sonata, Op. 101. To the attentive listener, he made its unexpected turns and deviations from traditional sonata form sound amazingly logical and even welcome. His graceful account of the opening movement was sheer poetry, to which his jocular approach to the following march movement with its athletic cross-hand figurations gave apt contrast. In the sonata’s formidable finale, Goode unleashed its powerful, ebullient themes with welcome panache, making the grand fugue Beethoven sneaks in at the development section even more surprising.

Between Bach and Beethoven, Goode inserted Schoenberg’s 1911 atonal suite, using its spare, highly concentrated motifs to evoke the transcendent aura of a vast, ancient temple. I found more mystery in Goode’s evanescent account of these short pieces than in playing through all of the pious piano music Erik Satie wrote at that same period for his Parisian Rosicrucian adepts.

Goode filled his program’s second half with a collection of Chopin Nocturnes and Mazurkas, as well as the Ballade No. 3 in A-flat Major, Op. 47, and the F-sharp Major Barcarolle, Op. 60. In quiet moments such as the B Major Nocturne, Op. 62, No. 1, his melodies unfolded with sensuous curves and shaded cadences that suggested either erotic or nostalgic overtones. But the aura of the salon disappeared with Goode’s more commanding release of the drama and grand themes of the Third Ballade. Four rather bland mazurkas played back to back seemed like unnecessary padding, but I admired the almost orchestral sweep of Goode’s buoyant account of the capacious Barcarolle in F-sharp Major, which ended his Chopin set.

For an encore, Goode offered a crisply defined account of William Byrd’s Second Pavane and Galliard from his famous collection My Ladye Nevells Booke.

The recital was presented by the La Jolla Music Society on Saturday, November 11, 2017, at the Irwin M. Jacobs Qualcomm Hall in Sorrento Valley.