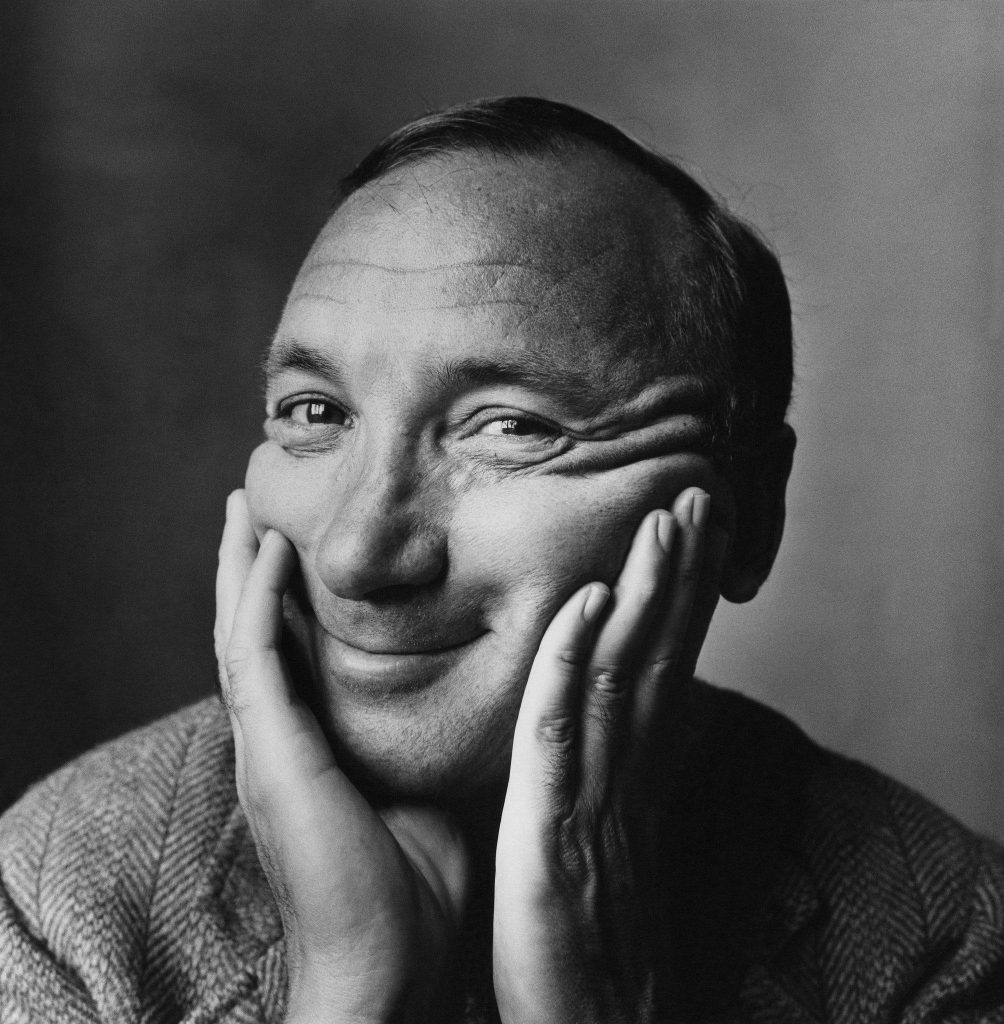

Neil Simon (such as he was)

Neil Simon’s Cheshire-cat grin, which died with him on Aug. 26, said a lot about his mechanics as a playwright. Public media image.

For those familiar with the mid-20th century’s Sid Caesar and Phil Silvers, news of the four-time Tony winner’s death came as a benchmark. Millions who saw Simon’s more than 30 plays and enjoyed Jack Klugman and Tony Randall in TV’s The Odd Couple were similarly affected, lauding Simon for what they found to be his unerring ear and eye in holding up the vagaries of the American fabric.

His casts paid tribute by the scores. Matthew Broderick, who played Felix Ungar in 2005’s The Odd Couple Broadway revival, said, ‘‘The theater has lost a brilliantly funny, unthinkably wonderful writer, and even after all this time I feel I have lost a mentor, a father figure, a deep influence in my life and work.” Nathan Lane, the show’s Oscar Madison, declared, ‘‘I am so proud to have played a small part in his unparalleled career and remarkable legacy.’’

[Neil Simon is] tailor-made for radio and TV audiences who think that theater is cut from the same utilitarian cloth.

The country’s writing contingent is also that much poorer, said screenwriter Randi Mayem Singer, as quoted in the Aug. 26 issue of newser.com:

‘‘If you write comedy, if you write period, you learned something from Neil Simon.’’

She’s right. I certainly did.

I learned to recognize when an author relentlessly backs into his characters and, even better, when he makes comedic mountains out of the molehills they were precisely designed to become.

I learned the difference between polishing gags and developing characters and how to trick audiences into believing that the former passes for humor.

I learned how to morph my giddiness as a ’50s TV writer (Simon worked alongside Caesar and Silvers and, before that, ‘40s radio man Goodman Ace) into dialogue that washes into the unsupervised marketplace, tailor-made for radio and TV audiences who think that theater is cut from the same utilitarian cloth.

I certainly did.

Theater is a game of inches and finesse, kind of the way football counts on both brawn and sleight of hand to advance the ball and disrupt an opponent’s game plan. It’s an adversarial pursuit for sure, with protagonists and antagonists jockeying for position in advancing the causes and personality traits they consider authentic.

And the best theater depends on an almost bureaucratic devotion to order and procedure in its appeal to the greater number.

Simon unceasingly (and ever so maddeningly) put the cart before the horse . . .

Compare that with Simon’s Biloxi Blues, the middle play of his Brighton Beach Memoirs trilogy, whose stock character Eugene Jerome comes of age during World War II basic training; or The Sunshine Boys, about an old-time vaudeville duo who reunite despite the fact that they can’t stand each other; or Barefoot in the Park (which concludes its extended run at The Old Globe Theatre on Sept. 16), centering on Corie and Paul, their fledgling marriage, a nosy mother-in-law and the earnestly hard work it takes to get a marriage right:

All and more are painfully built amid the success of their gags alone — the nuances to the hard-drinking platoon leader, the duo’s 47 years in vaudeville, the fact that fastidious Paul refuses to go barefoot in Washington Square Park — at the expense of the characters themselves. Simon unceasingly (and ever so maddeningly) put the cart before the horse, creating his people from his colossal cache of one-liners and the subtexts they generate. The theater’s enduring figures evolve as clean slates first, leaving plenty of time and logistics for development; Simon’s interminable violations are a stock in trade, almost as if he were concerned for his status should he venture into the systematic and left-brained.

Marvin Neil Simon couldn’t have painted a frontal character if he had a spray can and an automatic nozzle. Ever.

And in sanction to his sycophantic throng two generations strong, Biloxi Blues won two Tonys! Huh?!?

George (David Ellenstein) leans in as Jennie Malone (Jacquelyn Ritz) doesn’t object in North Coast Repertory Theatre’s ‘Chapter Two,’ from 2015. Photo by Aaron Rumley.

It was based on widower Simon’s relationship with second wife Marsha Mason until their marriage — the script’s heartfelt properties rang true, and text and subtext played off one another the way they should.

But man, Simon’s methods were universally antithetical. Maybe TV’s novelty (which produced greats like Steven Allen and Dave Garroway) had sabotaged his better angels in a kind of Stockholm Syndrome muddle, wherein unflagging devotion to unprecedented formula meant nothing less than otherworldly fame.

After all, his Lost in Yonkers scored a Pulitzer.

And he has a festival devoted to the preservation of his works.

And he has three honorary PhDs, including a Doctor of Law.

And he was the only living playwright whose name marked a Broadway theater.

Given his criminally overrated execution and his downright juvenile character development, let’s hope the restrooms are up to code.

Martin Jones Westlin is a San Diego Story theater critic and the principal at Words Are Not Enough editorial consultancy.