Masterworks from China’s Suzhou Museum at SDMA

If parts of Stonehenge and paintings by both Michelangelo and Raphael were at the San Diego Museum of Art, would you go? Objects as mysterious as Stonehenge and artwork as great as those by the famous Renaissance masters are all apart of Chinese history. Stonehenge, a colossal arrangement of stones in Great Britain, is still unknown as to why it was made but the grand effort to erect eighty 5-ton “bluestones,” which came from 200-miles away, and seventy-five 50-ton “sarsens,” which came from 23-miles away, makes the stone-age monument a Neolithic period wonder. Two of the some of the earliest examples of Neolithic carved jade stones from China called “Bi” (pronounced bee) and tubular “Cong,” which are just as mystifying and just as challenging to make as the 50-ton sarsens at Stonehenge, are now on display at the San Diego Museum of Art (SDMA) in Balboa Park.

The exhibition entitled Masterworks in Metal, Ink, and Silk from the Suzhou Museum on display through March 17th features treasures from the Suzhou Museum, located sixty-six miles west from Shanghai. It houses an encyclopedic trove of historic artworks from every period of China’s over 7,000-year history—including its stone-age Neolithic Liangzhu period (ca. 3500-2250 BCE), the Bronze Age era Shang Dynasty, the Classical Greece and Rome-like Zhou and Han Dynasties, the Renaissance-like Ming Dynasty, through to the last, most recent Qing Dynasty. The city of Suzhou is often referred to as the “Venice of China” because of its famed canals, gardens, and artistic legacy.

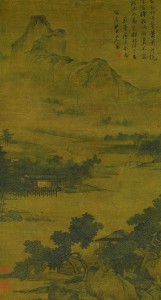

Ming dynasty (1368–1644). Tang Yin (1470–1523). “Illustration of Farming Maxims.” Ink on silk. Image courtesy of the Suzhou Museum.

The middle of the Ming Dynasty is viewed as a period of revival for Chinese art with the founding of the Wu School in the south. After a conservative darker period of occupying Mongolian rulers and conservative early conservative Ming Dynasty rulers, the Wu School is similar to the Western Renaissance in both time and circumstance. The four most famous artists of the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644 CE) are referred to as the “Four Masters of Ming” of whom three were associated with the Wu School of painters. Two artworks by two of the most famous artists from the Ming Dynasty are included in the SDMA exhibition, which was guest curated by art historian Suzanne Cahill from the University of California, San Diego.

The brown jade (jade with a high iron content) Neolithic period Bi on display is a minimalistic half-inch thick flat round disk approximately six-inches across with a 1.25-inch hole in the center. Jade is extremely difficult to sculpt due to its high content of the fibrous mineral asbestos and may be carved only by abrasion or it will fracture into tiny pieces. The only known method of producing such an object from this time period is to erode the surface with sand.

To cut the thin slab of jade, Neolithic cultures used wet sand as an abrasive to tediously grind away back-and-forth using a string saw to eventually free it from a larger chunk of jade. To produce the perfect circular hole, probably bamboo was laboriously rubbed back and forth between the maker’s hands like a drill, also using wet sand as the grit, to bore through the hard, brittle jade. The disk was then further polished to remove the gouge marks made from the string saw.

The Bi on exhibit at the museum is one of the earliest known examples of the form as it was excavated from the Laingzhu Archaeological Site (which borders China’s Jiangsu and Zhejiang Provinces) dating to ca. 3500–2250 BCE—where the earliest examples of Bi have ever been discovered. The jade itself probably came from the Yangtze delta region located 50-miles away. This early specimen shows the remarkable ingenuity and tenacity in using such simple tools to produce such a modern looking object.

The ritual significance of the Neolithic Bi are currently unknown but are found in burial tombs. Later in Chinese history during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE), Bi were placed near the head and feet and/or chest of human remains potentially as a portal for the afterlife spirit to reach the celestial realm.

The other equally mysterious object from the stone-age Laingzhu culture is the jade Cong. It is a rectangular prism-shaped tube. To make one of these objects would involve incredible effort and time meaning that that they were extremely important to the Laingzhu culture. The wide, cylindrical hollow of the tube was created in the same manner as the round hole in the Bi. The outside corners of the exterior of the prism shape features small, stacked rows of carved stylized face masks. When found in excavations of burials, tall Cong have been found lying on their sides lying end-to-end ringing an entire burial plot.

The brown jade Cong on display from the Suzhou collection is a rarer tall example of the form. Although, the masks, on the outside corners of this mighty Cong are simpler than smaller versions of this type of object. Owing to extreme size and the prodigious amount of time it would take to produce such an object probably some “corners were cut” to reduce the time to make something that was going to buried with the dead, which would explain the simpler type of masks on the Cong’s exterior corners.

Considered one of the greatest national treasures of China, a painting by Ming Dynasty master Tang Yin (1470—1523 CE) is on display in the exhibition. Tang Yin is the second of the “Four Masters of Ming.” The earliest and Yang’s teacher was ground breaking, more experimental Wu School founder Shen Zhou, akin to Leonardo Da Vinci. The Wu School was famous for its scholarly “literati” paintings featuring the “Three Perfections”: calligraphy, painting, and poetry.

Tang Yin had a notorious past being accused of cheating on the civil service exam and was barred from a lucrative job in the civil service. As such, he relied on selling his art to survive. Tang was gifted in his “running script” calligraphy and poetry, which he included in his slightly more conservative style paintings that were made for the commercial market. Tang Yin was more attuned to the earlier Yuan Dynasty (1280–1368 CE) styles of art. Like Renaissance artist Michelangelo Buonarroti and his goal to compete with the classical Greek and Alexandrian sculptors of the past. Tang is the Ming Dynasty equivalent of Michelangelo because of his desire to compete with the earlier, more classical Yuan masters.

The “Michelangelo of Ming’s” painting on display is considered by Asian scholars as his greatest work from his middle age. Painted on silk, Tang’s “Illustration of Farming Maxims” depicts a small village with rice crops flanking the Yangtze river in Jiangnan county with people fishing, reading, and playing chess. The upper left background features a snaking, sinuous mountain.

Overall, Tang’s painting features an impressive use of wet on wet style of loose, vivid brushwork to create slightly out-of-focus distant landscape and trees. His snaking background mountain, accomplished with brevity, uses just a few light washes and a few precise lines to define the contours. The foreground features the master’s renowned rocks formed from simple concentric lines expanding outward and looking like the surfaces of oyster shells. In the upper right, written in his famous running script is a poem:

“In Bashan village, the elders

Desolately voice strong complaints;

The officials send down new instructions,

But the people in the district can’t bear them.

Accusations enter ten-thousand households,

As everyone replants the green sprouts.”

When actually looking at the painting, the viewer’s eye languidly traverses the painting from bottom to top in left to right and back again sensuous rhythmic curves ending at the poem. Painting as poem. Poem as painting. Perfect!

Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). Wen Zhengming (1470–1559). “River through the Mountains in May.” Hanging scroll. Image courtesy of the Suzhou Museum.

Wen Zhengming (1470-1559) was a civil servant at the Hanlin Academy performing secretarial and literary tasks for the court. After retiring from civil service he withdrew to master the Three Perfections. He also studied with Shen Zhou, and Wen’s artistic accomplishments cemented the renown of the Wu School. He also had a talent for his ability to assimilate quickly four differing styles of painting. As such, he could be likened to the Renaissance master Raphael who was also quick in his ability to appropriate new styles. Wen also a excelled in landscape design helping to create the famous “Humble Administrator’s Garden” in Suzhou, which is listed as a World Cultural Heritage site.

Painted on paper, which is typical of the Wu School, Wen’s painting “Illustration of the Depths of the (Yangze) River during the Fifth Month” was painted in the second sunny day in the spring of 1536 after a cold winter when the artist was 67-years old. The painting is pristine although originally had some color that has now dulled. It is a stylized landscape that features a few metaphoric simple hut-like pavilions representing the leisure classes retiring to the simple life. The painting is set in the mountainous headwaters of the Yangtze River.

Laid out in the formal court style it has clear defined lines in the foreground trees. In the middle-ground are pine trees where every pine needle is individually painted with quick, tiny brushstrokes each applied with metered cadence. The painting also features his unique “grotesque” brushwork bravura in the rocks studding the banks of the river, but the best grotesque brushwork in the painting depicts a deformed, dorsal fin-like mountain in the upper-half of the artwork.

The Raphael-like master Wen manages to blend all these differing styles and textures of brushwork into a rich harmonious composition where a viewer can appreciate every inch of the painting from both extremely close-up and from farther away.

Other notable works in the exhibition are a ceremonial bronze Warring States period (450–221 BCE) “Ding” tripod cooking vessel with an ornate string pattern design and a Ming Dynasty silk embroidered scroll with the popular Chinese heroic General Guan Yu with needle work so fine that the stitching is virtually invisible. Other fine works are two Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) gray earthenware sculptures of attendant figures—especially good because of its more specific facial detail is one attendant holding a bird.

In summing up Masterworks in Metal, Ink, and Silk from the Suzhou Museum (from 15 December 2012 through 17 March 2013) at SDMA; the exhibition will surprise you when walking into the gallery because of the small gallery space. While a small exhibition with only twenty-one works, the tiny exhibit is a veritable jewel box filled with exceptional objects. The term Masterworks used to describe this exhibition is not hyperbole. If one actually meticulously scrutinizes each work on view with one’s own eyes, instead of through the viewfinder of a camera or cell phone, a viewer will be rewarded with potential hours of sumptuous pleasure by looking at all the fine details of the work on display.

© 2013 Kraig Cavanaugh

A great review! Not only doesCraig Cavanaugh entice the reader to go see the exhibit with his brilliant first paragraph-Michelangelo, Raphael and Stonehenge indeed- but then he proceeds to give an exceptionally fine, scholarly review. The very well researched background allows the reader , now eager to see the exhibit, to enjoy the works against the historical background in a context which would have eluded all but dedicated chinese art aficionados.

The San Diego Museum is to be congratulated on managing to acquire such outstanding Chinese works for exhibition.