History Gets Short Shrift, But ‘Black Pearl Sings!’ Radiates Great Chemistry

Folk and blues guitar legend Huddie William Ledbetter had one of those given names that rest irksomely on the tip of everybody’s tongue — mention his handle Lead Belly (bestowed by a brothel madam in a 1976 biopic), and the conversation immediately makes more sense.

Ledbetter’s legacy features his profound musical influence on figures from Jimmie Rodgers to Johnny Cash to The Beatles, his numerous appearances on early radio shows (one of which he helmed), his prowess as a self-taught musician who took to the road from his Louisiana home as early as age 16, his two stints in prison and his hard-won pardon in 1925, which he requested in a song he performed for the governor of Texas.

Susannah Mullally (Allison Spratt Pearce, left) and Alberta Johnson (Minka Wiltz) aren’t as different as they think. Photo by Daren Scott.

Please do enjoy the wondrous chemistry and the colossal vocals that color the two-character story, feting the unlikely relationship between the females involved.

While you’re at it, you may find yourself wondering why the original play is characterized as such in the first place.

Alberta (Pearl) Johnson is black and ten years ensconced at a women’s prison farm in southeast Texas for murder and its extenuating circumstances (i.e., relieving her victim of his — um — stuff).

[A]mid Susannah’s gangly riffs, Alberta deadpans that “You ain’t never danced nasty.”

Her epiphany is about to take shape courtesy Susannah Mullally, a lily-white Library of Congress musicologist who seeks to anthologize African American ballads and folk songs lest history overlook them for good.

Alberta will stop at nothing to see her 22-year-old daughter; childless Susannah exploits Alberta’s impulse by promising a reunion if Alberta will but collaborate on her project. The women tentatively trade jabs and (sort of) break the ice during Alberta’s “Little Sally Walker” — amid Susannah’s gangly riffs, Alberta deadpans that “You ain’t never danced nasty.”

Alberta is pardoned on the strength of a signature song, trading her black and white stripes for the finery that dots the New York lecture circuit. For her part, Susannah can’t afford the distraction Alberta presents, as she’s on the short list for a post at Harvard.

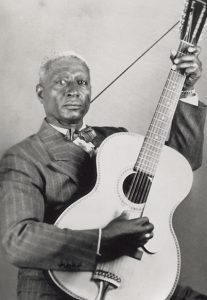

His roily past may have undercut Lead Belly’s musical genius. Public domain image.

Tragedy strikes soon after, not only redefining the women’s mutual trust but marking generations of lore that recast a newly enlightened Alberta.

Playwright Frank Higgins, a San Diego High School grad, might be a bit of a music historian as well — he’s deftly woven the mid-19th-century’s so-called Negro song landscape with its middle-Irish counterparts and quasi-spiritual appeals to the heavens. And while it might be argued that the play doubles as a showcase for Alberta’s actor, Higgins has made certain that Susannah retains a strong subtextual presence of her own.

That’s when it finally occurs that this play’s already been written — courtesy Ledbetter’s life itself. The switches in gender and setting; the daughter’s elusiveness; the efforts of one musicologist versus a team of music scholars: These elements merely shift focus rather than echo the history beneath them.

[Minka Wiltz’s] Mahalia Jackson vocals. . . define her Alberta to her core.

Indeed, Ledbetter enjoys a fairly prominent place in American folk music lore (everybody knows of some of his tunes, such as “Goodnight, Irene,” “Rock Island Line” and a cluster of others); a bioplay that examines the man himself might have been a more educationally useful tool. Higgins’ wholesale reimagining waters down the very history that seems to have launched his idea in the first place.

Please understand that this takes absolutely nothing away from the first-rate Minka Wiltz, whose Mahalia Jackson vocals (“No More Auction Block for Me,” “Troubles So Hard”) define her Alberta to her core. She lands Alberta’s initial mix of suspicion and curiosity about Susannah perfectly as the latter (Allison Spratt Pearce) wields her own formidability when it’s called for.

Pearce is very good indeed, although her innate physicality might read slightly on the willowy side for some. Even so, director Thomas W. Jones II has fleshed out each character’s cadence to a T.

Set designer Sean Fanning, lights maven Sherrice Mojgani and projectionist Victoria Petrovich read each other’s minds in enhancing the action. Ditto for sound designer Matt Lescault-Wood, music director S. Renee Clark and costumer Mary Larson, whose work illustrates each woman’s weaknesses and strengths.

Director Thomas W. Jones II knows a thing or two about character and cadence.

History — not its secondhand mirror — is where the anecdotes reside and always have.

This review is based on the opening-night performance of Nov. 29. Black Pearl Sings! runs through Dec. 17 at The Lyceum Space, 79 Horton Plaza downtown. $25-$72. 619-544-1000, sdrep.org.