David Roussève/REALITY Brings 1940s African-American Jazz Clubs to Life

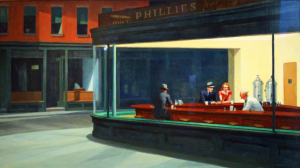

“Niighthawks” by Edward Hopper

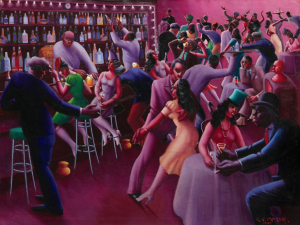

Adjacent paintings at the Art Institute of Chicago offer dramatically contrasting perspectives on American life in the 1940s. Edward Hopper’s “Nighthawks” (1942) is a portrait of alienation, with its lonely figures at the counter of a diner. A few steps away (the last time I visited the Art Institute), Archibald J. Motley Jr.’s “Nightlife” (1943) shows an African-American club so riotously lively, you can almost hear the music. Motley is said to have done his painting as a response to “Nighthawks,” and the message is clear. The white people at the diner may be at the top of the racial pecking order, but guess who’s having all the fun?

“Nightlife” by Archibald J. Motley, Jr.

Both paintings came to mind, watching “Halfway to Dawn” by David Roussève/REALITY, presented by UCSD ArtPower on Friday. The wonderfully ambitious, if over-reaching, piece is a sort of dance-biography of jazz great Billy Strayhorn. Much of the dancing, to Strayhorn classics like “Take the A-Train” and “Lush Life,” has the vitality of the Motley painting. The moves are celebratory and abandoned, a flung arm taking someone into an off-kilter turn. You want to join the nine dancers at the party.

David Roussève/REALITY in “Halfway to Dawn.” Photo: Rose Eichenbaum.

Yet, as we learn from text (written by Roussève) that appears on a video screen, Strayhorn himself was never entirely at the party. An openly gay man, he made his career in the jazz world in the 1930s through 1960s, and Roussève suggests that, at least in part due to homophobia, he got far less recognition than his talent deserved. He spent years in the shadow of Duke Ellington, who gave him a steady income but also put his own name on Strayhorn compositions. And Strayhorn’s heavy drinking and smoking contributed to his death from esophageal cancer in 1967.

In “Halfway to Dawn,” as everyone gets wild, there’s often one person who stands alone at the back of the stage, facing away, as separate as Hopper’s “Nighthawks.” A man shouts “Fun! Fun! Fun!” but it feels as if he’s trying too hard; and, as the piece proceeds, he sounds desperate. A clown does a merry jig in a video but later becomes a tragic figure.

“Halfway to Dawn.” Photo: Rose Eichenbaum.

Two dancers loosely represent Strayhorn and Ellington. Both of them happen to be named Kevin, a coincidence that gets played with onstage, and both are spectacular movers. Kevin Le, the smallish man who plays Strayhorn, is compact and quick, and he’s poignant as the sad clown. Tall, rangy Kevin Williamson, as Ellington, is big yet graceful, and it’s hard to take your eyes from him. Both men, like many in the outstanding cast, are graduates of UCLA’s Department of World Arts and Cultures/Dance, where Roussève is a professor.

The piece uses dance, music, spoken word, text, and video images (created by Cari Ann Shim Sham) shown on a large screen: a burning cigarette, the bell of a trumpet mouth, champagne glasses, what look like blood cells. There’s also footage of the 1960s civil rights movement—in which Strayhorn was deeply involved—shown on two smaller screens onstage, although I couldn’t see them. (Here’s where I get in my kvetch about the refurbishing of Mandeville Auditorium. How could any theater designer imagine it was smart to eliminate the raking in the front section?)

“Halfway to Dawn.” Photo: Rose Eichenbaum.

There are a lot of elements to weave together, and this ambitious project didn’t entirely succeed. The dancing and music were exuberant, and I came out knowing a lot about Billy Strayhorn, but I felt more educated than transported. The play among the dancers—chatting as they put on costumes, calling out, “Kevin! Kevin!”—created an inviting society onstage; it also felt like a distraction. And I wish Roussève had gone beyond the trope of the sad clown and come up with something more particular.

That said, it was thrilling to experience the magnitude of Roussève’s vision. If “Halfway to Dawn” fell short, that’s because it reached so high.

While this was a one-night-only program, there are three more ArtPower dance offerings coming up this season. Beijing Dance Company will be here January 30. Ephrat Asherie Dance February 28, and MacArthur grant-winning tap artist Michelle Dorrance brings her company to town on May 15. I saw Asherie at Jacobs Pillow Dance Festival last summer and Dorrance in Los Angeles, and both were well worth the trip.

Spot on review. And I was impressed with glorious arms twisting but was unable to see their legs or feet. Felt like I was was seated in a swimming pool. Mandeville was never a great dance venue, and now it’s worse.